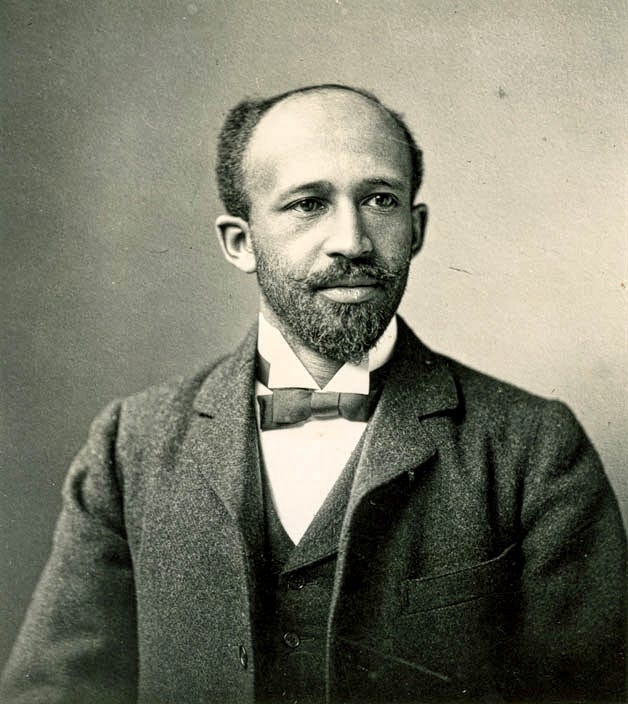

W.E.B. Du Bois, on Harriet Tubman and John Brown.

One of America’s most gifted intellectuals; a tireless freedom fighter working against unbelieveable odds; and a fiery man of conscience. Three American heros.

W. E. Burghardt Du Bois (1868–1963) published his biography of John Brown in September 1909, just six years after the publication of his most well-known work, Souls of Black Folk. John Brown emerged at a transition point for Du Bois as he moved from academia to pursue social activism, a transformation through which Du Bois became “the most influential civil rights leader of his time.”

“A full century has passed since John Brown started in America the Civil War,” Du Bois wrote in the Preface for the New Edition. The Civil War, he continued, “abolished legal slavery in the United States and began the emancipation of the Negro race from the domination of white Europe and North America.”

Du Bois drew on several other biographies of Brown for his work. “The only excuse for another life of John Brown,” he wrote in the original 1909 Preface, “is an opportunity to lay new emphasis upon the material which they have so carefully collected, and to treat these facts from a different point of view.” The point of view Du Bois adopted was “that of the little known but vastly important inner development of the Negro American.” Du Bois wanted to explore the friendships and collaborations between Brown and his companions and collaborators, not just as historical figures but as women and men of full conscience.

“John Brown worked not simply for Black Men — he worked with them,” Du Bois wrote. “…he was a companion of their daily life, knew their faults and virtues, and felt, as few white Americans have felt, the bitter tragedy of their lot.”

One particular relationship of note, aside from that of Brown’s collaboration with the great Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), was his interaction and collaboration with Harriet Tubman (1822–1913) with whom, Du Bois notes, Brown met in March or April of 1858.

Sarah H. Bradford’s biography, Harriet, the Moses of Her People, was published in 1886. Du Bois uses Bradford’s insights (drawing from Bradford’s pages 118–119) for his own description of the great Underground Railroad conductor, in John Brown (pages 186–187).

Brown had made his first trip to Canada and was staying in St. Catherines, Ontario, where he was to meet with Tubman. Du Bois describes the meeting of Captain Brown and General Tubman in one long paragraph, focused mostly on a dream in which Tubman seems to have foreseen Brown’s struggle to take Harper’s Ferry:

He stayed at St. Catherines until the 14th or 15th, chiefly in consultation with that wonderful woman, Harriet Tubman, and sheltered in her home. Harriet Tubman was a full-blooded African, born a slave on the eastern shore of Maryland in 1820. When a girl she was injured by having an iron weight thrown on her head by an overseer, an injury that gave her wild, half-mystic ways with dreams, rhapsodies and trances. In her early womanhood she did the rudest and hardest man’s work, driving, carting, and plowing. Finally the slave family was broken up in 1849, when she ran away. Then began her wonderful career as a rescuer of fugitive slaves. Back and forth she traveled like some dark ghost until she had personally led over three hundred blacks to freedom, no one of whom was ever lost while in her charge. A reward of $10,000 for her, alive or dead, was offered, but she was never taken. A dreamer of dreams as she was, she ever “laid great stress on a dream which she had had just before the met Captain Brown in Canada. She thought she was in ‘a wilderness sort of place, all full of rocks, and bushes,’ when she saw a serpent raise its head among the rocks, and as it did so, it became the head of an oldman with a long white beard, gazing at her, ‘wishful like, jes as ef he war gwine to speak to me,’ and then two other heads rose up beside him, younger than he, — and as she stood looking at them, and wondering what they could want with her, a great crowd of men rushed in and struck down the younger heads, and then the head of the old man, still looking at her so ‘wishful!’ This dream she had again and again, and could not interpret it; but when she met Captain Brown, shortly after, behold he was the very image of the head she had seen. But still she could not make out what her dream signified, till the news came to her of the tragedy of Harper’s Ferry, and then she knew that the other two heads were his two sons.”

In Tubman, Du Bois writes, “John Brown placed the utmost confidence.” Brown was recollected as saying that “General Tubman, as we call her” was “one of the best and bravest persons on this continent.”

Only sickness, Du Bois writes, “brought on by her toil and exposure, prevented Harriet Tubman from being present at Harper’s Ferry.”